With the introduction of common-interest-developments some 50 plus years ago, came the requirement of Reserves: the long-term maintenance and replacement contribution plan for the common areas.

At this time the personal computer and spreadsheets did not exist. Common area reserve items were tracked manually on column pads with a pencil, calculator and eraser. The very basic reserve item data was collected: description, cost, estimated useful life and in how long was it scheduled to be replaced next or the remaining life. This was entered on the pad and then a basic assumption was made: the beginning balance of reserve funds was allocated between the individual reserve items.

Next was a straight-line calculation was made taking the cost of the individual reserve item and subtracting it’s allocated beginning balance of reserve funds producing the unfunded balance that would be needed at the schedule time of the maintenance or replacement. The unfunded balance was then divided by the remaining life (years) calculating the reserve contribution for this item.

This was repeated for all the reserve items and the contribution from each reserve item was summed giving a total contribution. A simple calculation accepted by all.

This was obviously a tedious task with a pencil, a calculator and an eraser. By the early 1980’s the personal computer and the first spreadsheets were to make this process much easier and faster. It is probably safe to say that a majority of the reserve planners had stepped up to this new technology by the end of the 1980’s. This was the standard accepted calculation and because it was the standard it didn’t even have a name.

In 1989 the concept of a cash flow was introduced to the reserve study industry. It used the same data that was derived in the past but went a step farther in not just taking into account of when the next scheduled time of maintenance or replacement would be but also when the recurring maintenance or replacements would occur. This calculated projected maintenance or replacement expenditures was done for a desired number of years. At the end of the 1980’s this was usually for 20 years.

Based on the projected expenditures for the 20 years and knowing the beginning balance of reserve funds and a determined interest rate to be earned on the reserve funds, a contribution was produced with performing a “what if scenario”: if we enter this initial amount for the contribution in the first year and the following years, will there be sufficient reserve funds over the next 20 years for the projected expenditures which would also project a continued positive balance of reserve funds?

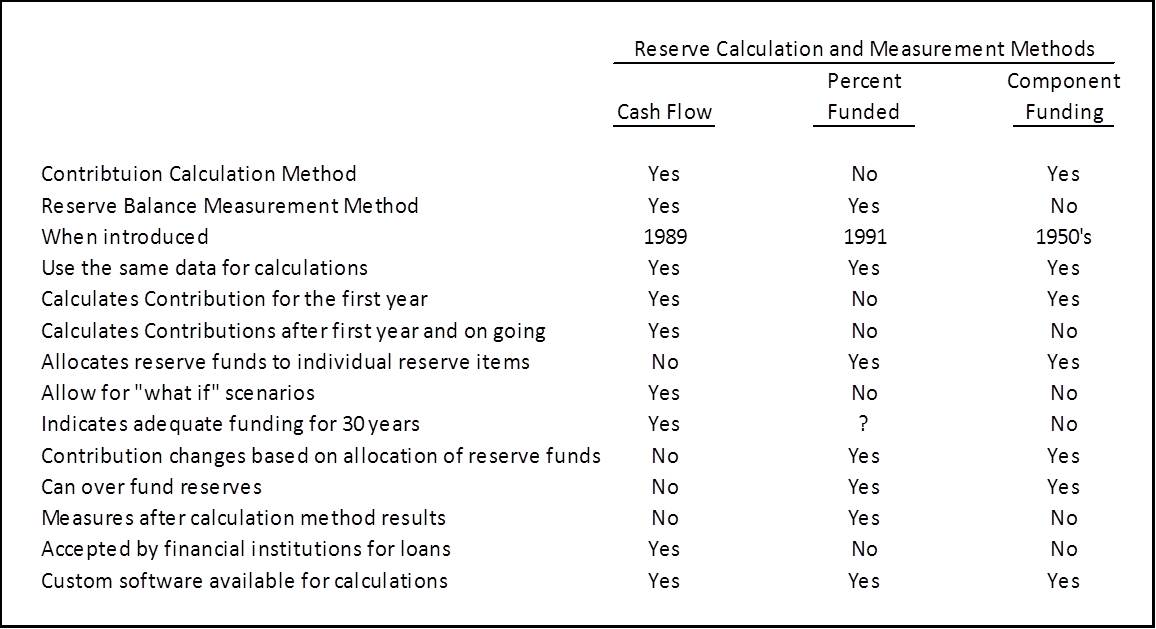

Hence, an alternative method of calculating the reserve contribution, the Cash Flow method, to be compared to what would be known as the Component Funding method as described above. The biggest difference between these two methods is that the Component Funding method allocates the beginning balance of reserve funds between the individual reserve items where the cash flow method does not.

After comparison analysis of these two methods with the help of spreadsheets, some previously unnoticed problems were found with the Component Funding method:

1) It only calculated the contribution for the first year,

2) If you changed (or re-shuffled) the allocation of the beginning balance of reserve funds between the individual reserve items, a different contribution would be calculated each time, and

3) The initial calculations did not take into account interest earned on reserve funds or inflation on reserve items.

When the interest earned on reserve funds and inflation on reserve items was acknowledged, the Component Funding method spreadsheet was adapted to try to take these into account. But the shortfalls on only calculating the contribution for the first year and if you re-shuffled the beginning balance of reserve items between the individual reserve items that a different contribution would be calculated still existed.

As an evolution of the Component Funding method came Percent Funding, which many consider to be another reserve funding contribution calculation method. Percent Funding is not a contribution calculation method but an evaluation or a measurement of a reserve funding plan. As the Component Funding method, the Percent Funded was also produced on a straight-line calculation as follows:

If a reserve item has a 10-year estimated useful life and a current cost of $10,000 and has been in service for 4 years, then to be a 100% Funded $4,000 should exist in reserve funds for this reserve item. Percent Funding is easily presented for both calculation methods, Component Funding and Cash Flow.

Based on Component Funding presents each reserve item with its own reserve fund balance, the Percent Funded is calculated by dividing the reserve fund balance by the 100% funded calculated number as presented above.

For the Cash Flow method, the 100% funded amount is calculated for each reserve item and totaled. The beginning balance of reserve funds is then divided by the 100% funded amount total. The main difference between these two presentations is that the Cash Flow presentation will continue to present the 100% funded amount and percentage for the future desired number of years where Component Funding only presents for the first year.

In the early 1990’s the first reserve study software became available in which it made it possible to see reiterations of Component Funding and Cash Flow side by side using identical reserve item data. This was also the time when terminology and semantics started being created about reserve studies which helped to create the opinions and confusion which still exists today. The following are some of these terms:

Ideal Balance, Theoretical Ideal Balance, Fully Funded, 100% Funded, Baseline Funding, Threshold Funding, Full Funding, Statutory Funding, Percent Funding and the list goes on.

If these terms were given to five reserve study preparers you would probably not get a consensus of what these terms mean or how are they related. Some will say that Ideal Balance, Fully Funded and 100% Funded all mean the same thing and some will say they don’t. Welcome to reserve study politics.

But what should be uncontested is that Baseline, Threshold, Full and Statutory Funding are all defined reserve goals/plans which are calculated and presented in a Cash Flow and do not relate to Component Funding. As established by CAI:

- Baseline Funding: Establishing a reserve funding goal of keeping the reserve cash balance above zero.

- Threshold Funding: Establishing a reserve funding goal of keeping the reserve fund balance above a specified dollar or percent funded amount. Depending on the threshold, this may be conservative than full(y) funding.

- Full Funding: Setting a reserve funding goal of attaining and maintaining reserves at or near 100% funded.

- Statutory Funding: Establishing a reserve funding goal of setting aside the specific minimum amount of reserves required by local statues.

These goals/plans descriptions are probably useful for management or the board of directors of an HOA giving direction to a reserve study preparer of what they would like to achieve.

Not much has changed since the mid to late 1990’s about the above except the continued arguments if percent funded actually indicates anything. But what has continued to happen in the last two decades is no consensus on any of the above (except maybe defined goals/plans). Individual States have gone off on their own and determined their own criteria of requiring what calculation method should be used and what should be presented in a reserve study report.

As more and more States have or are preparing statutory reserve study reporting requirements, they are looking at what other States have done and the domino effect of confusion spreads. Current national HOA and reserve study associations will not address these issues. There has been some attempt by Federal agencies (FHA, Fred Mac and Fred Mae) to avoid the recent financial mortgage debacle into the future, but nothing yet that will set a definitive standard that would override at a minimum current individual State requirement.